Navigating Bonus Depreciation for “Flip-Flop” States

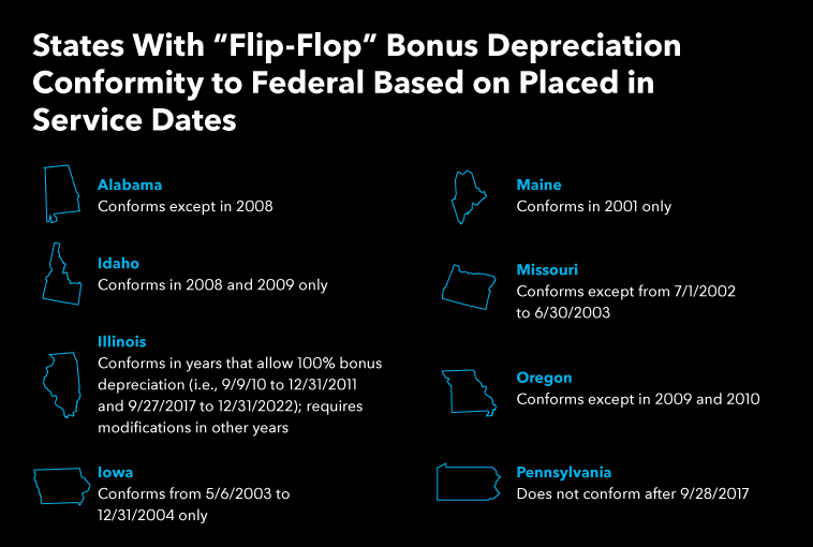

“Flip-flop” states, or those that have gone back and forth between conforming and not conforming with federal tax laws are particularly problematic for tax and accounting professionals, especially when it comes to bonus depreciation.

Dec. 22, 2021

By Ryan Sheehan, Senior Product Lead

for Bloomberg Tax & Accounting.

Corporate taxation has never been an easy task. This is especially true for those that oversee corporate state tax compliance as states do not consistently conform to the Internal Revenue Code (IRC). The passage of the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) added to this challenge by creating significant uncertainty regarding the states’ response to “full expensing” (i.e., the new 100

Caption: Companies with assets in “flip-flop” states should determine whether there are any depreciation impacts in open tax years and continue to monitor these states due to their complexity.

Calculating and Tracking State Taxable Income

While most states use federal taxable income as a starting point, each state imposes certain addition or subtraction modifications to arrive at state taxable income. For states that do not conform to bonus depreciation, additional calculations are required. Keeping track of these modifications over time is critical because the additions and subtractions change each year and ultimately sum to a net modification to state taxable income.

Additionally, many states require state tax forms that may require detailed supporting documentation. Plus, some states require reported modifications to be broken out by type of depreciation (e.g., Section 179, bonus depreciation, regular MACRS), while others require a single modification amount to reconcile the difference between the total federal and state depreciation. There are also a handful of states that have their own unique depreciation schedules, and some that require a separate Form 4562 for state depreciation purposes as if bonus depreciation had not been claimed.

Pennsylvania, for example, has had a long history of complexity when it comes to calculating bonus depreciation. This state requires corporations to compute depreciation for property placed in service after Sept. 27, 2017, under the regular Modified Accelerated Cost Recovery System (MACRS) rules, without regard to bonus depreciation. For property placed in service prior to Sept. 28, 2017, Pennsylvania allowed federal bonus depreciation, but only with an addback of bonus and plus a 3/7 formula. To underscore the complexity in calculating Pennsylvania’s bonus depreciation, consider the example below.

Asset #1

- Cost: $300,000

- Recovery period: 3 years

- Depreciation method: Straight-line

- Placed-in-service date: January 1, 2017

- Federal bonus depreciation: 50% of 300,000 = 150,000

- Federal regular depreciation: 150,000/3 = 50,000

- State regular depreciation: 50,000 x 3/7 = 21,429 [in 2019, asset is fully depreciated for federal purposes, so PA allows deduction of remainder (150,000 – 21, 429 – 21,429 = 107,142)]

Asset # 2

- Cost: $300,000

- Recovery period: 5 years

- Depreciation method: Straight-line

- Placed-in-service date: January 1, 2018

- Federal bonus depreciation: 100% of 300,000

- Federal regular depreciation: 0

- State regular depreciation: 300,000/5 = 60,0000

Modifications in Subsequent Tax Years

For most companies, Excel is the go-to tool used to keep track of these complicated modifications. However, as tax and accounting professionals chartered with managing bonus depreciation can attest to, the pitfalls of Excel – time-consuming, error-prone and cumbersome – apply more than ever. One way to combat some of the Excel challenges is to maintain separate depreciation books for each state with the correct bonus depreciation configurations by period. While still time consuming, this approach enables taxpayers to compare the detailed depreciation differences from the federal and state books without manually tracking and accumulating modifications from year to year.

Determining Gains and Losses: State and Federal Differences

Typically, an asset’s adjusted basis is equivalent to its cost reduced by the depreciation allowed or allowable over the life of the asset. To determine regular depreciation under MACRS, an asset’s adjusted basis is first reduced by the bonus depreciation amount.

Consequently, a state that does not allow (also known as non-conforming) bonus depreciation creates differences in federal and state adjusted basis. As such, maintaining accurate records is critical. This is because when it comes time to dispose of the asset, any accumulated basis differences will result in a difference between the gain or loss reported at the state and federal levels.

Rather than track modifications to state depreciation over time to arrive at state adjusted basis, maintaining a separate state depreciation book can reduce reconciliation times and help to ensure accuracy. Consider the example below.

- Cost: $1,000,000

- Recovery period: 7 years

- Depreciation method: 200% declining balance

- Placed-in-service date: January 1, 2020

- Disposal date: December 31, 2021

- Disposal proceeds: $800,000

- The state in question does not conform to bonus depreciation

Computation of Adjusted Basis at 12/31/2021

Gain Computation Differences for Tax Year 2021

Looking to the future, calculating asset depreciation for flip-flop states will not likely get any easier. If your company only has a few assets to manage, then a singular Excel database is a reasonable solution. For large companies with thousands of assets across multiple states to track, creating separate depreciation books for each state is still extremely time consuming, error-prone and cumbersome, but at least taxpayers are able to compare the detailed depreciation differences from the federal and state books without manually tracking and accumulating modifications from year to year. In addition, rather than track modifications to state depreciation over time to arrive at state adjusted basis, maintaining a separate state depreciation book can reduce reconciliation times and help to ensure accuracy. The ultimate solution, however, is depreciation software that has state depreciation rules built in and stays up to date with new tax laws automatically.

=====

Ryan Sheehan is a Senior Product Lead for Bloomberg Tax & Accounting. He is responsible for Bloomberg Tax & Accounting’s corporate tax products, including Fixed Assets. Prior to Bloomberg Tax & Accounting, Ryan was a CPA at KPMG’s Washington D.C. Metro office in the Business Tax Services practice.